If you need proof that the Arab Spring has turned the Middle East upside down, dwell for a moment on the irony that Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s Islamist President, has managed to put the U.S. and Israel at ease even as he has filled many of his compatriots with dread.

On becoming Egypt’s first democratically elected leader on June 30, Morsi included non-Islamists in his Cabinet, ignored religious extremists’ calls for restrictions on secular liberties, curbed the power of the military and refrained from populist economic policies. He even quit his membership in the Muslim Brotherhood to strengthen his claim to represent all Egyptians. Abroad, he maintained the 33-year-old Israel-Egypt peace treaty and tried to persuade Syrian tyrant Bashar Assad to step down. In November, he leveraged the Brotherhood’s long-standing relations with Hamas to broker a cease-fire between the Palestinian group and Israel, winning international kudos in the process.

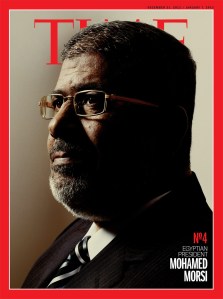

(PHOTOS: Morsi’s Life in Images)

The very day after the Gaza cease-fire took effect, however, Morsi sparked massive protests across Egypt when he announced an emergency decree granting himself more powers. The Egyptian revolutionaries who had toppled former President Hosni Mubarak immediately accused Morsi of reclaiming the dictator’s powers. Some of the protests that followed turned deadly. Morsi dropped the emergency decree but insisted that a hastily written draft constitution be put to a national referendum. Its most controversial sections define, in ambiguous terms, the extent to which Egypt will be governed by Shari‘a, or Islamic law.

For all his troubles at home, Morsi remains the Middle East’s most influential figure. He alone has the clout to keep Hamas in line with the cease-fire agreement; having brokered the deal, he now has the responsibility to ensure that the Palestinian group refrains from firing rockets into Israel. Egypt, along with Turkey, continues to press for an end to the slaughter in Syria and will play an important role in shaping any post-Assad transition. A more assertive Egypt can also be a stabilizing counterweight to Iran’s ambitions in the region. And Morsi’s handling of his country’s constitutional crisis will provide pointers for all the other Arab Spring states — and any aspiring to join their ranks — on the real prospects for Islamist democracy.

Two years after a self-immolating Tunisian fruit vendor set off the protests that would turn into revolution, the countries where the old order was toppled are, like Egypt, struggling to create order out of their new circumstances. In most places, Islamist parties were better prepared for the democratic process than the liberal revolutionaries and easily won elections; but governing — the business of managing an economy, creating jobs, fighting corruption, removing the remnants of the old regime — is proving much harder.

(INTERVIEW: A Conversation With Mohamed Morsi)

The hardest task of all? Defining the nature and laws of the newly democratic state. Like Egypt, the other Arab Spring countries want new constitutions, and in Tunisia as much as in Egypt, liberals are demanding an outsize voice in the process. In Libya and Yemen, the two other Arab Spring countries with new governments, it’s the Islamists who are agitating for a bigger say. In all these countries, the two sides disagree vehemently — and sometimes violently — on the role Islamic law must play in governance.

So far, Egypt is a cautionary tale, a study in how not to write a new constitution. Morsi’s liberal opponents are not entirely blameless: they have been intransigent and often hysterical in their opposition to any expression of the country’s Muslim identity. But the President’s Islamist brethren, who dominate the constituent assembly, have failed to heed the anxieties of the liberals and the country’s minorities, who rightly fear legalized persecution. Throughout, Morsi has shown a reluctance to rein in his former colleagues and allay the misgivings of his opponents. His actions have raised the inevitable question: Is this Islamist just an imperfect democrat or an incipient dictator?

I can’t shake the feeling that much of Egypt’s tumult might have been avoided if Morsi had extended to his fellow citizens the courtesy he has shown me. When we first met, in the summer of 2011, he was chairman of the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP), the new political offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood. Photographer Yuri Kozyrev and I were at an FJP office, a modest residential apartment in a nondescript Cairo district, to meet another official, when Morsi walked into the waiting room. Since his colleague wasn’t around, he took it upon himself to keep us company, ignoring an aide’s repeated reminders of important phone calls and meetings. With a courtly solicitousness, he asked how we were coping with the heat and whether we had been away from home long. He inquired about our nationalities (Yuri is Russian, I’m Indian) and found complimentary things to say about our respective countries.