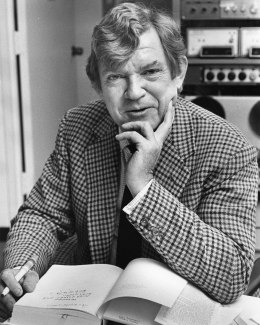

At some early point in his long career, more than three decades of it spent at TIME, Robert Hughes became the most famous art critic in the English-speaking world. This happened because he was also the best — the most eloquent, the most sharp-eyed and incisive, the most truculent and certainly the most robust. He was 74 when he died on Aug. 6. As Auden put it after the death of Yeats: “Earth, receive an honoured guest.”

Very simply, Hughes was better than anyone else of his generation in deciphering and explaining art’s great paradox and its fundamental enchantment: that a mute object, a painting or statue, can be eloquent about the world. And he did it in language that could be as rich as Shakespeare’s and as merciless as Jonathan Swift’s. You could disagree with Hughes, you could find some of his positions aesthetically reactionary, but you could not be bored by him.

Hughes was one of Australia’s most famous exports. His 1988 book The Fatal Shore is probably the best-known history of how the continent was settled as a penal colony. But it was The Shock of the New — an immensely popular eight-part television series and the still indispensable book of the same title that grew out of it — that changed everything. Tracing the history of modern art from post-Impressionism to Warhol with detours into architecture, it was broadcast by the BBC in 1980 and by PBS in the U.S. the following year. It attracted 25 million viewers and brought Hughes a kind of cultural celebrity even great critics don’t usually achieve.

Hughes had powerful enthusiasms. He adored Goya and Bonnard and the late, great Lucian Freud, the British painter he did much to introduce to an American audience. He was no less famous for his thundering discontents. He practiced art criticism as a contact sport complete with tackles and head butts, and as the years went by he found more and more to dislike about contemporary art. The postmodernism of the 1970s, with its coy appropriations from the past, struck him as trifling and academic. He liked even less the slapdash neo-Expressionism that lumbered through the galleries of SoHo in the 1980s. His dismissals of David Salle and Julian Schnabel, two of its chief load bearers, were choice. (“Schnabel’s work is to painting what Stallone’s is to acting: a lurching display of oily pectorals.”) By the ’90s, he was comparing the output of New York City artists to the strident and derivative Late Mannerism of 16th century Rome: “Garrulous, overconceptualized and feverishly second hand.” And in the art market’s frenzies he saw nothing more than a scramble for status by insecure billionaires chasing brand-name operators like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst.

I became his successor — you succeed Bob Hughes; you don’t replace him — and every day his voice still sounds in my head. Throughout his career, Hughes produced that rare thing, journalism that will last, some of the best of it collected in his book Nothing if Not Critical. Every week, in the pages of this magazine, he was a one-man Augustan age. To return again to Auden on Yeats: upon his death, Yeats “became his admirers” — meaning he was kept alive by his readers. Likewise Hughes. In his lifetime, he had plenty of them. So long as there are people who love art, the study of history and the English language, he always will.

This text originally appeared in the Aug. 20, 2012 issue of TIME magazine.