Their life hummed along, but there were moments that reminded them that they were different. When the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center sent the couple a check to pay back a loan, Windsor recalls being afraid to cash it at her bank. They didn’t always feel comfortable in some parts of the gay community, which at the time had its own prejudices. One night at a bar in the Hamptons, responding to criticism from gays who disapproved of how the couple’s relationship divided into masculine and feminine roles, Spyer stood on a table and said, “If you don’t have room for me butch and her femme, then you don’t have a movement.” In 1977, Spyer was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, but she continued to work. Around that time, Windsor left IBM after 16 years to travel and volunteer for gay community organizations.

Robert Maxwell for TIME

Roberta Kaplan, Windsor’s attorney, believed she was the right plaintiff.

The 1980s were, of course, a brutal decade for the gay community. AIDS decimated the gay male population, and disapproval of gay sex reached a historic high. A 1988 Gallup poll found that 57% of Americans thought gay sex should be illegal. Windsor lost friends, but she says AIDS, like Stonewall, ultimately brought the community together. “Lesbians lived in one world, and the gay men lived in another world. Then when the AIDS crisis happened, the lesbians flocked in to wait on people and to nurse them. So all of a sudden, that wall came down. We were looking at a much greater hunk of our population and loving it.”

As the gay-rights movement got stronger, opponents of equality pushed back harder. Public sentiment toward gay people in the 1990s seemed to take one step forward and two steps back. In 1993, after campaigning on a pledge to lift the military’s ban on gays, President Bill Clinton brokered a compromise that made “Don’t ask, don’t tell” official U.S. military policy. That same year, Spyer and Windsor registered as domestic partners when it became possible in New York. When Ellen DeGeneres filmed her coming out on her sitcom in 1997, Time marked the event on its cover—with a photo of DeGeneres captioned “Yep, I’m Gay”—and noted that bomb-sniffing dogs had been brought in to check the TV show’s set. In 1998, Matthew Shepard, a gay college student in Wyoming, was tortured and murdered.

In 1996, Congress passed, and Clinton signed, the Defense of Marriage Act for the purpose, according to the House, of expressing “moral disapproval of homosexuality, and a moral conviction that heterosexuality better comports with traditional morality.” The law defined marriage for federal purposes as a union between a man and a woman and declared that states would not be required to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states.

At first glance, DOMA might have seemed little more than a rubber stamp of the status quo. No states permitted gay marriage in 1996, and according to Gallup, 68% of Americans were against it. But some members of Congress were concerned that gay marriage was on the move. Hawaii’s courts appeared ready to support gay marriage; a backlash caused legislators there to pass one of the first two (along with Alaska’s) state constitutional amendments targeting gay marriage in 1998. Though marriage had been a goal for some since Stonewall, other gays in the movement considered it either a pipe dream or an antiquated institution that could distract from other, more important issues like employment and housing discrimination or the AIDS crisis. Unsuccessful court challenges on behalf of gay marriage in the ’70s led gay groups like the Human Rights Campaign to focus their energies on other things.

The movement didn’t gain momentum until the spring of 2004, when Massachusetts became the first state to legalize gay marriage. Opponents, meanwhile, won 11 state constitutional amendments banning gay marriage, while Karl Rove turned it into a wedge issue for President George W. Bush. Though the movement suffered a big loss in California with the passage of the anti-gay-marriage Proposition 8 in 2008, it soon made gains that had seemed impossible a decade earlier. In 2009, gay marriage became legal by court ruling in a Midwestern state, Iowa, and by legislative votes in New Hampshire and Vermont. It passed with Republican votes in New York’s legislature in 2011 and by popular vote in 2012 in Maryland and Maine.

Meanwhile, in 2007, after Spyer got a bad prognosis related to a heart condition, which she would eventually die of, she and Windsor decided to go to Canada with the help of a filmmaker and gay-marriage activist who had become an expert at shepherding gay couples across the border to get married. It was not an easy trip for Spyer, whose worsening MS had made her quadriplegic by that time. When their wedding announcement ran in the New York Times, dozens of people from Windsor’s past life—including old IBM colleagues who finally learned that she was gay—called to congratulate her.

Robert Maxwell for TIME

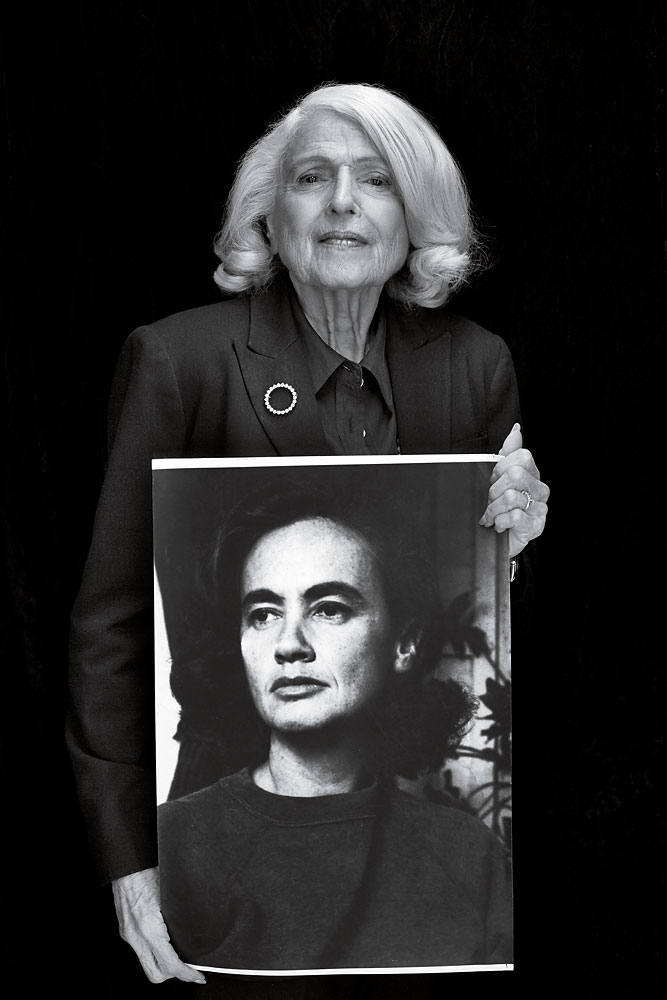

Windsor with a picture of her late Spouse

Spyer died quietly at home in 2009. Brokenhearted, Edie was hospitalized with a heart attack. She was then served with a $363,053 estate-tax bill on property that Spyer had left her. Spouses are exempt from the estate tax, so Windsor filed for a refund from the IRS. It was denied. Because of DOMA, the federal government didn’t recognize her marriage.

Furious, Windsor did what so many other ordinary gay people in her generation had been forced to do in response to adversity: she decided to fight. After gay-rights organizations turned her down—they worried, among other things, that she was too privileged to serve as the face of an important case—she connected with Roberta Kaplan, a lesbian and corporate litigator at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, who had argued in favor of gay marriage before New York’s highest court. In their 2010 suit, Windsor and Kaplan argued that DOMA violated the constitutional right to equal protection. The momentum was with them. In 2011—for the first time in history, according to Gallup—a majority of Americans supported legalizing gay marriage. In 2012, when the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Windsor’s favor, Windsor told Time, “The amount of dignity that just fell off onto people was incredible.”

A Time For Joy

It is difficult to overstate the practical benefits to every gay American following Windsor’s victory in June. After the Supreme Court decision, gay couples could file joint tax returns, get access to veterans’ and Social Security benefits, hold on to their homes when their spouses died and get green cards for their foreign husbands and wives. For many couples—especially those with children and those without means—these benefits and protections are not merely symbolic. At the beginning, for Windsor and Kaplan, the case was about getting Edie her money back.