Francis also moved early to tame the mess that is the Vatican Bank, an institution even U.S. Treasury officials privately say is corrupted. Soon after he was elected, he named a special commission to investigate the bank, which in turn handed the matter off to an independent firm for an audit. Francis also issued initiatives to counter money laundering and increase the monitoring of the Vatican’s finances. In October, the bank disclosed an annual report for the first time in its 125-year history.

And if personnel is policy, Francis has been particularly busy, shaking up the Curia with his preference for new faces over old ones. In a move that signifies he means business, he tossed Benedict’s Secretary of State, Tarcisio Bertone, and named ambassador to Venezuela Archbishop Pietro Parolin, the youngest man to hold the post since Eugenio Pacelli, who went on to become Pope Pius XII in 1939.

In April, Francis tapped a boarding party of eight like-minded bishops from around the world to meet with him several times a year to comb through difficult problems, a move that diffused some of the traditional power of the Synod of Bishops. “I don’t want token consultations,” he explained in an interview, “but real consultations.” That, at least so far, appears to be what he is getting. The membership is telling: Cardinals from Chile, Congo and Honduras as well as Munich, Australia and Boston are on the panel. In August, another member, Cardinal Oswald Gracias of India, issued one of the most expansive comments about gays that the church has ever made, stating that while the church does not allow gay marriage, homosexuality is not a sin. “To say that those with other sexual orientations are sinners is wrong,” he wrote to an LGBT group in Mumbai. “We must be sensitive in our homilies and how we speak in public and I will so advise our priests.”

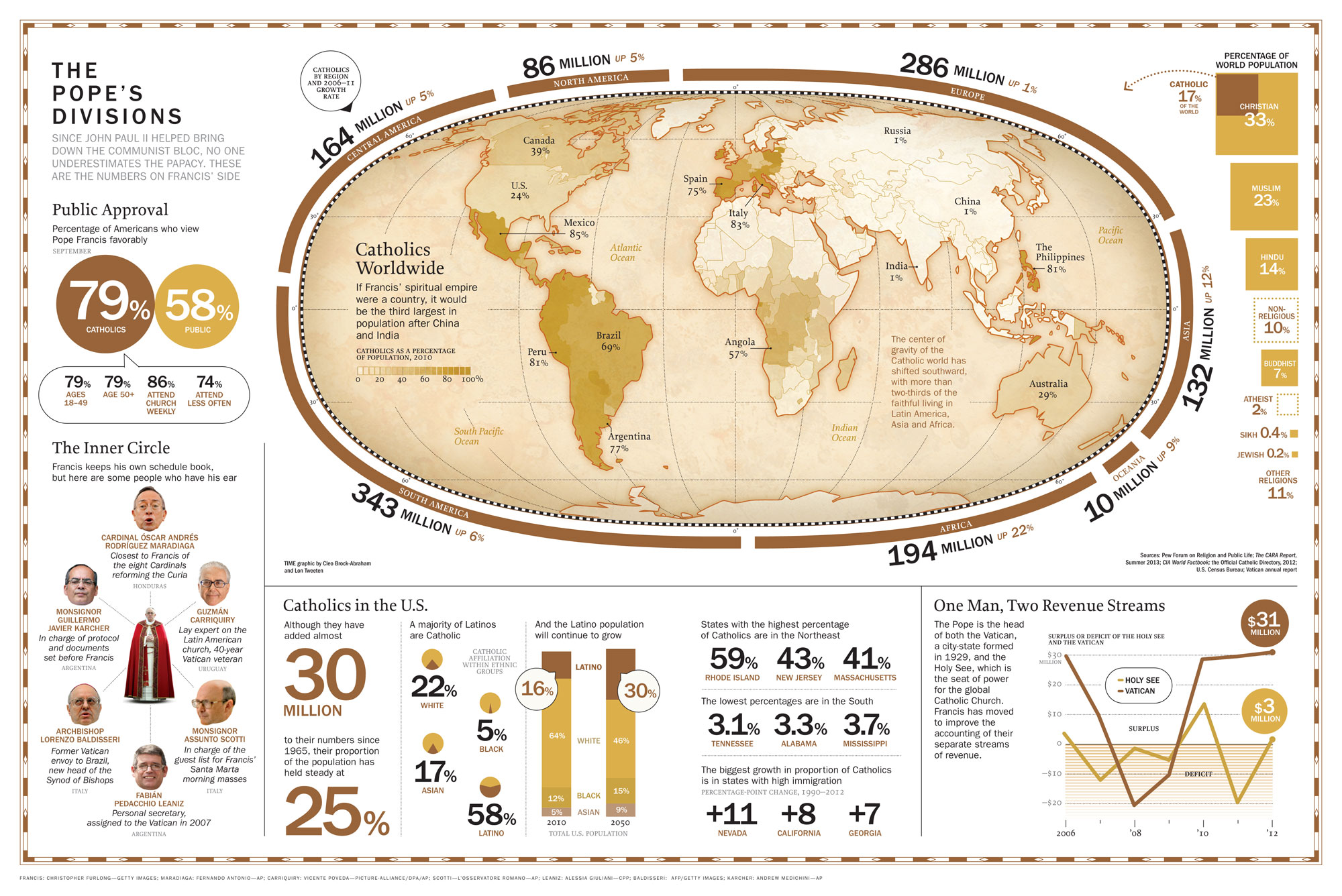

↳ Click to enlarge | TIME Graphic by Cleo Brock-Abraham and Lon Tweeten

And on Dec. 5, in a long overdue move, the group of eight named a new commission on sex abuse, the problem of priests preying on children they had vowed to protect. It is the church’s darkest existential problem in an era of existential problems; the commission aims to study better ways to protect children, screen programs that involve children and suggest new ways to create safe environments and choose the priests to lead them. At worst, the Cardinals are laying out a new set of best practices for far-flung dioceses to follow. At best, they are admitting that the Vatican had focused too much attention on the legal challenges of the sex-abuse crisis rather than on the behavioral problems at its core.

Francis has backed up his deeds with homilies and his first apostolic exhortation. He can barely contain his outrage when he writes, “How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?” Elsewhere in his exhortation, he goes directly after capitalism and globalization: “Some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion … has never been confirmed by the facts.” He says the church must work “to eliminate the structural causes of poverty” and adds that while “the Pope loves everyone, rich and poor alike … he is obliged in the name of Christ to remind all that the rich must help, respect and promote the poor.”

The church has always made the poor a priority—a mission that has been the biting paradox of the treasure-laden Vatican. But Francis has made it clear that they are a priest’s first responsibility. “A lack of vigilance, as we know, makes the Pastor tepid; it makes him absentminded, forgetful and even impatient,” he preached in May. “It tantalizes him with the prospect of a career, the enticement of money and with compromises with a mundane spirit; it makes him lazy, turning him into an official, a state functionary, concerned with himself, with organization and structures, rather than with the true good of the People of God.” In case anyone missed the point, he suspended a bishop in Limburg, Germany, for overseeing a $42.5 million renovation of the church residence that included a $20,500 bathtub. Says Father Guillermo Marcó, who was Bergoglio’s spokesman from 1998 to 2006: “It is the first time we have had a priest as Pope.”

An Argentine’s Way

On weekends in Buenos Aires, you can take a 31⁄2-hour bus tour of the neighborhoods where Jorge Mario Bergoglio grew up. “What’s coming up on this street?” the tour guide Daniel Vega asks as the bus pulls up on Calle Membrillar in the Flores district of Buenos Aires. “The house where he was born,” comes the answer. There’s the chapel where his father Mario, a native of the Piedmont region of Italy, and Regina, an Argentine of Piedmontese descent, met in 1934. They married the next year and had their firstborn, Jorge Mario, on Dec. 17, 1936.

The Bergoglios were very strict Catholics, the kind who worry about meeting people who were not married in the church or who were socialists or atheists. But the future Pope was never that doctrinaire: in the four years between realizing he was called to the priesthood and actually entering seminary, he said he had “political concerns, though I never went beyond simple intellectualizing.” He admits to reading and liking publications of the Communist Party but says he was never a member. Many Bergoglio watchers—a minor industry in Argentina—believe that his concern for the destitute is partly rooted in Argentina’s experience with Peronism, a strange socialist-capitalist amalgam that evolved in the country in the 1940s and was powered by a deep, working-class populism. That ideology suffused everything Argentine then—and now.

Bergoglio is quite mystical about his career choice, which hit him when he stopped off at church on his way to join friends to celebrate a holiday. “It surprised me, caught me with my guard down,” he told Francesca Ambrogetti and Sergio Rubin, who interviewed him for their 2010 book, published this year in the U.S. as Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio. “That is the religious experience: the astonishment of meeting someone who has been waiting for you all along.” He did not enter seminary until 1957, telling the authors, “Let’s say God left the door open for me for a few years.”

He was briefly a nightclub bouncer and would as a 21-year-old seminarian lose most of his right lung to an infection, a condition that may contribute to his back problems today. He chose to join the Jesuits because the order—founded as the Catholic Church launched the counterreformation—was at “the front lines of the Church, grounded in obedience and discipline.” He claimed to not be disciplined himself and thus in need of the structure. What he did have was a talent for empathy and for engaging people in conversation. Even before he was ordained, he was a popular and attractive figure to his students at Jesuit schools as well as to many superiors. In 1973, at 36—just three years a priest—he was named the head of the Society of Jesus in Argentina and the boss of Jesuits many years his senior. The office came with prestige, huge responsibilities and, as it turned out, the seeds of almost two decades of turmoil for himself, which nearly derailed his career.

His crisis centered around two Jesuits, Father Orlando Yorio and Father Francisco Jalics, who refused his orders over the period of about a year beginning in 1975 to leave the slums as the country spiraled into political chaos and the military, which considered slum priests to be likely rebels, was clearly moving to take over Argentina. As terrorists on the right and left tore the nation apart, many Argentines—including some bishops and priests—longed for a strong hand to reassert control over the country, and many welcomed the military coup of March 24, 1976.

In May the two Jesuits were arrested and subjected to torture. Bitterness has lingered among some Jesuits and the relatives of Yorio (who died in 2000), who to this day accuse Bergoglio of virtually giving up the priests to the junta, citing a flurry of bureaucratic paperwork that ultimately failed to provide cover for the clerics to stay on in the slums. Bergoglio said he immediately tried to win their freedom (as he would do for many others), and Yorio and Jalics were released after five months. Very few of the “disappeared”—as abducted Argentines were called—reappeared alive.

Even after Bergoglio served out his term as Jesuit provincial in 1979, he remained a divisive figure. In 1988, when he was serving as a theology lecturer at a school in Buenos Aires, he came into conflict with the provincial at the time, Father Victor Zorzín, who reassigned Bergoglio to Córdoba, more than 400 miles (640 km) northwest of Buenos Aires. From June 1990 to May 1992, according to journalist Elisabetta Piqué, author of the biography Francis: Life and Revolution, he could make no phone calls without permission, and his correspondence was “controlled.” Zorzín says “it cost [Bergoglio] a lot to accept the change. But pain can ripen into something else.”