In what would prove to be a providential turn, a Cardinal who admired Bergoglio’s work as provincial—including his ability to assess the talents of others and organize productive meetings—came seeking him and, rescuing him from Córdoba exile, turbocharged his ascent in the church hierarchy. And as he rose from bishop to Archbishop to Cardinal, Bergoglio began ministering to the slums—the same kind of districts that Yorio and Jalics refused to leave at his orders. Jalics, who now lives in Bavaria, kept silent about the case for nearly four decades but released a statement after Bergoglio became Francis, declaring that “Orlando Yorio and I were never given up by Jorge Bergoglio … I used to think we had been victims of an accusation. But by the late 90s, after many conversations, it was clear to me that I was wrong.”

After becoming Archbishop in 1998, Bergoglio was known for his frugality, for taking the bus and the subway and for living in a simple apartment on the same block as the cathedral, not at the opulent archdiocesan residence. That kind of humility increased his appeal not only with ordinary Argentines but also among his fellow Archbishops in Latin America. His meteoric postexile rise seemed to climax in April 2005, when the death of John Paul II brought Bergoglio to Rome and to the ranks of what Vaticanologists call I papabili—the Cardinals who might become Pope. The Wednesday after Germany’s Joseph Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI, Bergoglio had lunch with his press secretary Marcó and, according to Marcó, never let on that the Latin American Cardinals had gathered enough support to make him the runner-up in the conclave. Some accounts have Bergoglio signaling to his supporters to shift their votes to Ratzinger so as not to prolong the process and give an impression of a divided College of Cardinals.

He returned to Buenos Aires and looked to retirement. He had already picked out the residence where he would live out the rest of his life—an old-age home for priests in Flores, where he was born—and handed his letter of resignation to the Pope when he turned 75 in 2011. “I’m starting to consider the fact that I have to leave everything behind,” he said in 2010. “It makes me want to be fair with everyone always, to sign the final flourish … But death is in my thoughts every day.” He insisted he was not sad, and he went on posing for pictures with the faithful. But his face gave him away, and one parishioner called him on it: “Padre Jorge, if you’re going to put on that face, you’re going to ruin the photo.”

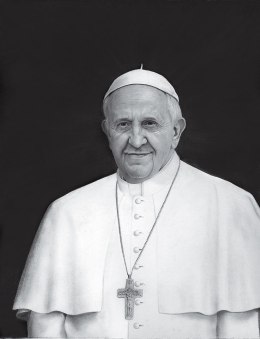

Then without warning on Feb. 11, Benedict XVI announced that he was abdicating the papacy, the first time a Pope had resigned in 600 years. The Archbishop of Buenos Aires once again flew to Rome, though he was no longer on the hot list of I papabili. But on the night of March 13, to the world’s surprise, Bergoglio emerged on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica as Francis.

Argentines saw on his face what millions of others could not have divined: the sad, haggard look was gone. Joy cometh in the evening.

Francis has made society’s most vulnerable—the sick, the elderly, immigrants and children—the focus of his ministry.

See more photos of the Pope made for Person of the Year on LightBox .

The Limits Of Reform

The five words that have come to define both the promise and the limits of Francis’ papacy came in the form of a question: “Who am I to judge?” That was his answer when asked about homosexuality by a reporter in July. Many assumed Francis, with those words, was changing church doctrine. Instead, he was merely changing its tone, searching for a pragmatic path to reach the faithful who had been repelled by their church or its emphasis on strict dos and don’ts. Years of working closely with parish priests have taught him that the church seemed more comfortable with narrow issues than human complexity, and it lost congregants and credibility in the bargain. He is urging his army to think more broadly. As he told Spadaro, “What is the confessor to do? We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods. That is not possible. I have not spoken much about these things and I was reprimanded for that. But when we speak about these issues, we have to talk about them in a context.”

In short, ease up on the hot-button issues. That might not seem like significant progress in the U.S. and other developed nations. But the Pope’s sensitivity to sexual orientation has a different impact in many developing countries, where homophobia is institutionalized, widespread and sanctioned. Similarly, Francis is aware of the liberal clamor in the affluent West for the ordination of women. He also recognizes that Catholic doctrine, as it is currently formulated, cannot be made to justify women as priests. “The feminine genius is needed wherever we make important decisions,” he has said. But that does not involve ordination as priests. Instead, in his recent exhortation, he says he wants to diminish the primacy of the all-male priesthood, arguing that just because they monopolize the sacraments does not mean their gender should be the only one empowered in the church.

That won’t make the grade for women who expect equal protection and rights under secular law. But the real significance of these new horizons will likely come in countries where the stakes for women are far higher than just the question of ordination. In the places where the Catholic Church is growing fastest, Francis’ words may portend significant advances in culture wars where women and other disadvantaged groups have always been on the losing side. When Catholic Archbishop Berhaneyesus Souraphiel of Addis Ababa talks of women in the church, he thinks of the crisis in sub-Saharan African regions where female genital mutilation is common. He is trying to rally Catholics to raise money to build a university where women can have greater access to education. Souraphiel sees great progress in Francis’ statements about women. “It could help a lot,” he says, “because he is saying women have a great role in the church and in society.”

But if there appears to be some wiggle room on homosexuality and the role of women, there is none for abortion. “This is not something subject to alleged reforms or ‘modernizations,’” Francis says. “It is not ‘progressive’ to try to resolve problems by eliminating a human life.” Even so, Francis’ tonal shifts on doctrine have unsettled some church conservatives, particularly in the U.S., where some bishops in the past have declined to offer Communion to elected officials who favor abortion. The exact size of this group is unknown, but no one denies it exists. “Already there has been a lot of backlash from traditionalist groups, conservative groups, people who feel he is moving too quickly away from the traditional style of Benedict on liturgy, on clerical appointments,” says Brian Daley, a professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame. “But that’s probably a relatively small group of people.”

Those who have inveighed against abortion and homosexuality for decades may fear that the ground is shifting underneath their feet. Some of the harshest criticisms of Francis have come from traditionalists alarmed at his emphasizing the Pope’s role as just another bishop—albeit of Rome—rather than Supreme Pontiff. They argue that this path would lead to the end of the papacy as the world has known it for centuries. In early October, Mario Palmaro, a conservative bioethicist who worked for Radio Maria, went so far as to co-author an essay titled “We Do Not Like This Pope” that hinted that Francis was the Antichrist because of his all-too-knowing use of the media to propagate heterodox ideas. Palmaro was particularly appalled by the interview Francis granted the atheist editor of the Italian daily La Repubblica, in which the Pope was quoted as saying, “I believe in God, not a Catholic God.” The station fired Palmaro for criticizing the boss. But in November, after Palmaro came down with a debilitating disease, Francis telephoned to console him. “I was so moved by the phone call that I was not able to conduct much conversation,” Palmaro told reporters. “He just wanted to tell me that he is praying for me.” Palmaro says he has not changed his opinion of Francis’ policy.

Part of the conservative critique is that Francis’ words and gestures cannot be fully reconciled with the legacy of previous Popes. Apparently aware of that potential for controversy, Francis has been skillfully citing the writings of former Pontiffs, stressing continuity. As the first Pontiff to be ordained a priest after Vatican II, he has been generous to the opinions of John XXIII, who convened that reformist council. But it is a delicate task given that Francis has one thing no Pope has had since the 15th century: a living predecessor. While Benedict resides in quiet retirement in the Vatican Gardens, he remains a potential rallying point for those who fear that Francis may hold the doctrinal reins too loosely. So far, Francis and Benedict appear to get on well: both men flatter each other, and Francis was especially generous with quotations from Benedict in his recent exhortation. In any case, Francis needs to keep his predecessor on his side, for it was Benedict who codified the conservative views of John Paul II, the hero of many Catholics, particularly those on the right of the spectrum.

Francis will continue the policy of both John Paul II and Benedict on détente and fraternal relations with Judaism. (Francis plans to visit Israel in May.) But with his experience working with the Muslim immigrant population of Argentina, Francis will extend a warmer hand toward Islam than Benedict, who famously infuriated that religion’s clerics with a scholarly aside in an otherwise innocuous speech. And he has proved himself amenable to Protestant, evangelical piety, scandalizing conservative Catholics in Argentina by kneeling and being blessed by Pentecostal preachers in a Buenos Aires auditorium.