A few years ago, a high-ranking U.S. intelligence official was asked what he most wanted to know about Bashar Assad, the Syrian leader. “Whether he’s Michael or Fredo,” he replied. “Whether Syria’s [leadership] is singular or plural.”

The Corleone reference, from The Godfather, was apt. The Assads have run Syria as a mafia family business since 1970, when Bashar’s father Hafez Assad gained control in a Baathist coup. The Assads are Alawites, a Shi‘ite-related minority sect, and Hafez Assad ruled his 80% Sunni country with a relentless brutality. In 1982 he put down a rebellion by the Muslim Brotherhood in the city of Hama, killing an estimated 20,000 people.

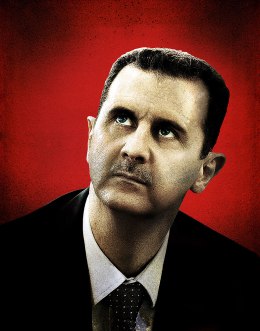

Bashar Assad was not expected to succeed his father. He had been trained in England as an ophthalmologist and was married to a stylish investment banker. His charismatic older brother Bassel was the designated successor, but Bassel died violently in a car crash, and when Hafez died in 2000, Bashar became a rather unlikely President of Syria.

He didn’t look like a tyrant. He was gawky-tall, soft-spoken, with a halfhearted mustache and milky blue eyes. At first, some in the U.S. intelligence community believed he was a front man for a family consortium that included his older sister Bushra and her husband General Assef Shawkat, who controlled the Syrian intelligence services; there was also a younger brother, Maher, an alleged hothead in charge of the army’s Republican Guard.

When I interviewed Assad in 2005, it was difficult to tell if he was Michael or Fredo or someone else entirely. He was not at all bombastic or egomaniacal; he seemed a bit nervous. And yet he was thoughtful, eager to engage in a real conversation rather than filibuster the interview, the usual modus operandi for despots. He sat slouched on a couch—not exactly the body language of an aggressor—and seemed boggled by his predicament.

He knew he was dancing through a minefield. President George W. Bush had sent the “with us or against us” message to the region after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and Syria was trying to be both and neither. The government had allowed a de facto safe haven for the funders of Iraq’s Sunni rebels and for assorted anti-Israel terrorist groups. The Syrian intelligence forces were suspected of abetting Hizballah in the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. And the Assads were Iran’s main ally in the region. Syria’s contradictory tangle of allegiances and private arrangements was, in fact, a perfect exemplar of the mind-numbing complexity of Middle East politics.

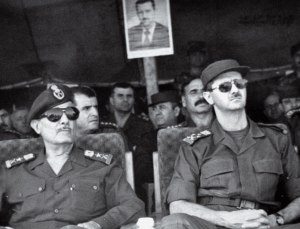

After his sudden appointment as president in 2000, Assad, right, relied heavily on advisers like army chief of staff Ali Aslan, left.

Assad talked wistfully about his desire to finish his father’s peace negotiations with Israel. He said he wanted to be a “good neighbor” in the region. He said he was intending to pull all Syrian troops out of Lebanon in the next few months—a statement immediately contradicted by his own government but which turned out to be true. As I was leaving, he said, “Send this message: I am not Saddam Hussein. I want to cooperate.”

That man—that slightly overwhelmed prisoner of the palace—seems very different from the Bashar Assad we’ve come to know. He is unquestionably Michael now. His brother-in-law, the intelligence director Shawkat, was killed in a Damascus bombing in 2012; his younger brother Maher was severely injured in another bombing. Bashar stands alone in the rubble, presiding over a regime that has surpassed the brutality of his father’s by orders of magnitude—an estimated 126,000 dead; more than 1,000, including over 400 children, killed by chemical weapons; hundreds of thousands wounded; more than 2 million refugees fled to neighboring countries. “He’s much worse than his father,” says Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations. “He has killed relentlessly and without any attempt to reconcile with his opponents. He seems to believe that if he just keeps killing them, they will eventually give up.”

Shrewdness and Savagery

It appears to be working. The tide has turned his way in the civil war that began in the Arab Spring of 2011. He has survived, even though the bulk of the world—except for Iran, Russia and China—wanted to see him deposed after his Aug. 21, 2013, chemical attack on the Sunni suburbs of East Damascus. He survived because, unlike Saddam, he had a very precise sense of his own mortality, a very precise sense of the steps needed to placate the U.S. and ensure his survival. In the process, he made Barack Obama seem irresolute and foolish, an American President who threatened military action, then backed down, then threatened again—before finally agreeing to a Russian-initiated deal to get rid of the Syrian chemical stockpile. There was great skepticism that Assad would actually cooperate in this process, but he had made several very clear-eyed military and political calculations of the sort that eluded Saddam and most of the other myopic despots in the region. He knew that if he didn’t adhere to the deal, Obama would have no choice but to obliterate the Syrian air force—and Assad needed the air force far more than he needed the chemical weapons; it was his primary enforcement mechanism in his war against the rebels. He also realized that by agreeing to the deal, the Obama Administration would tacitly acknowledge his legitimacy as the leader of Syria. The U.S. and the rest of the world would have to negotiate with him over the terms of the disposal. It was a move that would have made Michael Corleone proud.