A few years ago, a high-ranking U.S. intelligence official was asked what he most wanted to know about Bashar Assad, the Syrian leader. “Whether he’s Michael or Fredo,” he replied. “Whether Syria’s [leadership] is singular or plural.”

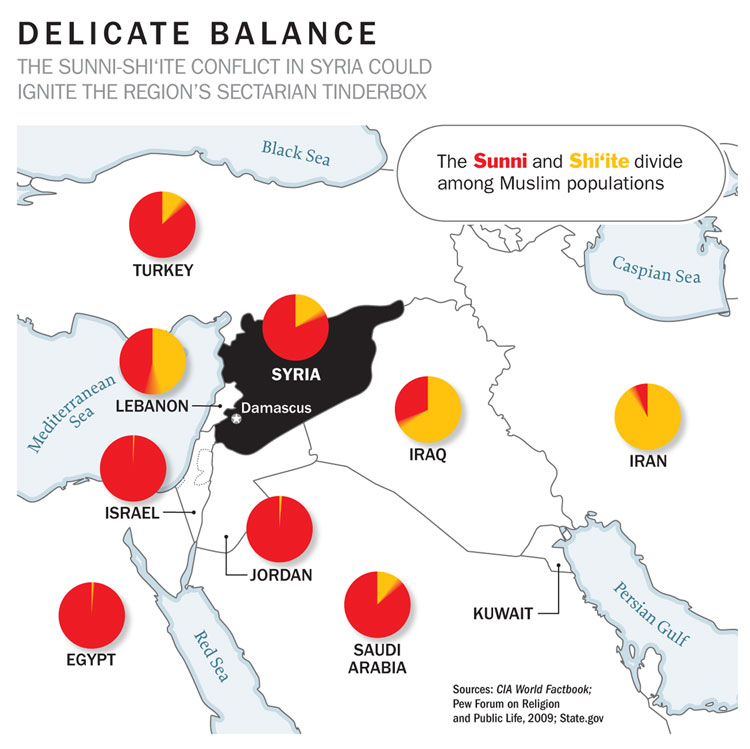

The Corleone reference, from The Godfather, was apt. The Assads have run Syria as a mafia family business since 1970, when Bashar’s father Hafez Assad gained control in a Baathist coup. The Assads are Alawites, a Shi‘ite-related minority sect, and Hafez Assad ruled his 80% Sunni country with a relentless brutality. In 1982 he put down a rebellion by the Muslim Brotherhood in the city of Hama, killing an estimated 20,000 people.

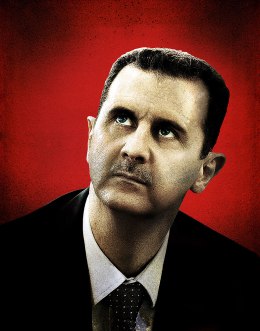

Bashar Assad was not expected to succeed his father. He had been trained in England as an ophthalmologist and was married to a stylish investment banker. His charismatic older brother Bassel was the designated successor, but Bassel died violently in a car crash, and when Hafez died in 2000, Bashar became a rather unlikely President of Syria.

He didn’t look like a tyrant. He was gawky-tall, soft-spoken, with a halfhearted mustache and milky blue eyes. At first, some in the U.S. intelligence community believed he was a front man for a family consortium that included his older sister Bushra and her husband General Assef Shawkat, who controlled the Syrian intelligence services; there was also a younger brother, Maher, an alleged hothead in charge of the army’s Republican Guard.

When I interviewed Assad in 2005, it was difficult to tell if he was Michael or Fredo or someone else entirely. He was not at all bombastic or egomaniacal; he seemed a bit nervous. And yet he was thoughtful, eager to engage in a real conversation rather than filibuster the interview, the usual modus operandi for despots. He sat slouched on a couch—not exactly the body language of an aggressor—and seemed boggled by his predicament.

He knew he was dancing through a minefield. President George W. Bush had sent the “with us or against us” message to the region after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and Syria was trying to be both and neither. The government had allowed a de facto safe haven for the funders of Iraq’s Sunni rebels and for assorted anti-Israel terrorist groups. The Syrian intelligence forces were suspected of abetting Hizballah in the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. And the Assads were Iran’s main ally in the region. Syria’s contradictory tangle of allegiances and private arrangements was, in fact, a perfect exemplar of the mind-numbing complexity of Middle East politics.

After his sudden appointment as president in 2000, Assad, right, relied heavily on advisers like army chief of staff Ali Aslan, left.

Assad talked wistfully about his desire to finish his father’s peace negotiations with Israel. He said he wanted to be a “good neighbor” in the region. He said he was intending to pull all Syrian troops out of Lebanon in the next few months—a statement immediately contradicted by his own government but which turned out to be true. As I was leaving, he said, “Send this message: I am not Saddam Hussein. I want to cooperate.”

That man—that slightly overwhelmed prisoner of the palace—seems very different from the Bashar Assad we’ve come to know. He is unquestionably Michael now. His brother-in-law, the intelligence director Shawkat, was killed in a Damascus bombing in 2012; his younger brother Maher was severely injured in another bombing. Bashar stands alone in the rubble, presiding over a regime that has surpassed the brutality of his father’s by orders of magnitude—an estimated 126,000 dead; more than 1,000, including over 400 children, killed by chemical weapons; hundreds of thousands wounded; more than 2 million refugees fled to neighboring countries. “He’s much worse than his father,” says Leslie Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations. “He has killed relentlessly and without any attempt to reconcile with his opponents. He seems to believe that if he just keeps killing them, they will eventually give up.”

Shrewdness and Savagery

It appears to be working. The tide has turned his way in the civil war that began in the Arab Spring of 2011. He has survived, even though the bulk of the world—except for Iran, Russia and China—wanted to see him deposed after his Aug. 21, 2013, chemical attack on the Sunni suburbs of East Damascus. He survived because, unlike Saddam, he had a very precise sense of his own mortality, a very precise sense of the steps needed to placate the U.S. and ensure his survival. In the process, he made Barack Obama seem irresolute and foolish, an American President who threatened military action, then backed down, then threatened again—before finally agreeing to a Russian-initiated deal to get rid of the Syrian chemical stockpile. There was great skepticism that Assad would actually cooperate in this process, but he had made several very clear-eyed military and political calculations of the sort that eluded Saddam and most of the other myopic despots in the region. He knew that if he didn’t adhere to the deal, Obama would have no choice but to obliterate the Syrian air force—and Assad needed the air force far more than he needed the chemical weapons; it was his primary enforcement mechanism in his war against the rebels. He also realized that by agreeing to the deal, the Obama Administration would tacitly acknowledge his legitimacy as the leader of Syria. The U.S. and the rest of the world would have to negotiate with him over the terms of the disposal. It was a move that would have made Michael Corleone proud.

Assad’s apparent survival will have an enormous, and perhaps surprising, impact on the Middle East. The massacre of so many Sunnis has certainly exacerbated the sectarian chasm in the region. Iran has won a victory in Syria and another victory at the nuclear negotiating table. Indeed, the Sunni calculus has Iran much empowered by the events of the year, including the ascension of the seemingly moderate, and temperate, regime of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif.

This, in turn, has created the potential for an unlikely new alliance in the region. The Israelis and the Saudis have long had near identical national-security interests; they have privately shared intelligence about the Iranian threat for years. The Saudis are worried about an Iranian nuclear weapon but also that Iran and Iraq will foment trouble in their Eastern province, home to most of the Saudi petroleum reserves—and also home to most of the kingdom’s Shi‘ites. The Israelis are worried not only about an Iranian nuclear weapon but also about the threat of Iran-supported terrorist organizations like Hizballah and Hamas.

The perception of Iran’s new strength is matched by a fear of U.S. weakness. Obama’s willingness to deal with both Assad and Iran has been blasted, publicly, by the Saudis and Israelis. Obama’s moves—plus the dwindling American need for Saudi oil—are seen as harbingers of a new era of war-sick timidity by the U.S.

Ten years ago, the Saudi crown prince promised to recognize Israel if it made peace with the Palestinians. There was some skepticism about this: the offer was made to New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman and not directly to the Israelis. But the possibility is not so unthinkable anymore. “Not only are there common security interests between Israel and the Saudis,” says Shai Feldman, an Israeli security expert and director of the Crown Center at Brandeis University, “but there is also a strong economic case to be made” for an alliance. Israel needs oil and markets; Saudi Arabia needs technology and the security provided by the most formidable—and nuclear-armed—military in the region. “Bibi Netanyahu’s economic dream has always been to be the Singapore of the Middle East,” Feldman says. “That dream may be within his grasp. Provided, of course, that he is willing to make the difficult decisions required to reach peace with the Palestinians.”

In fact, Netanyahu is now faced with an existential calculation similar to Assad’s: a peace deal with the Palestinians contains obvious security and domestic political risks—the West Bank settler movement is a powerful force in Israel; the Palestinians have always been recalcitrant in face-to-face negotiations. But diplomatic acceptance by the Arab League, and an implicit security alliance with the Saudis, would be a major step toward Israel’s dream of full acceptance in the region.

New Opportunities

The possibility of good news in the Middle East is almost always dashed by the preponderance of bad actors. The roadblocks to a grand bargain—not the least of which is the surreptitious Saudi funding of al-Qaeda and Wahhabi extremists—are prodigious. But the U.S. can help with clever diplomacy. John Kerry’s State Department has made a strong push for progress in the West Bank talks. The U.S. negotiating team recently added a significant player in David Makovsky, a regional expert who has drawn the most detailed and plausible maps for land swaps between the Israelis and Palestinians. There is speculation that the U.S. will put a comprehensive Middle East peace plan on the table in the summer of 2014, the first since Bill Clinton’s last-minute proposal at Taba in January 2001.

That would be a mistake. The U.S. has lost a great deal of stature because of Bush’s Iraq invasion and Obama’s vacillations. Its public actions in the region have seemed either clunking, neocolonial interventions; naive fantasies about democracy in countries without a substantial middle class; or hollow, unplanned rhetoric and dithering. A better role for the U.S. would be to use its convening power to mediate a deal privately, to nudge the Saudis and the Gulf states toward real economic and security arrangements with the Israelis and to reassure Netanyahu that he is acting in the best long-term interests of his country.

Assad’s survival in 2013 may have opened the door to new diplomatic possibilities in 2014, but the Syrian dictator should not sit easy on his contaminated throne. There is no guarantee that the current Syria will be the country that emerges from this period of upheaval. Already, the Syrian Kurds have joined with their Iraqi cousins in a de facto alliance—and the Iraqi Kurds are now selling oil directly to the Turks in defiance of the Shi‘ite government in Baghdad. The Sunnis of western Iraq and eastern Syria have found common cause as well. The straight-line borders, drawn in the sand by Europeans during World War I, may soon be revised by the people who actually live there. The likely consequence is another generation of turbulence, which will make the need for stable allies all the more important in the region.

But, for the moment, Bashar Assad—the mild-mannered ophthalmologist turned Old Testament tyrant—has taught his neighbors an ancient lesson: that absolute, unrelenting brutality combined with geostrategic cleverness is the most likely way to retain power in the Middle East.