Malala spent most of her pocket money on books, says the teacher. She carried a Harry Potter schoolbag and read a biography of Benazir Bhutto as well as one of Barack Obama’s books. One of her favorite books was Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, and she often quoted the well-known line about how the universe conspires to help when you want something.

(MORE: Barack Obama, 2012 Person of the Year)

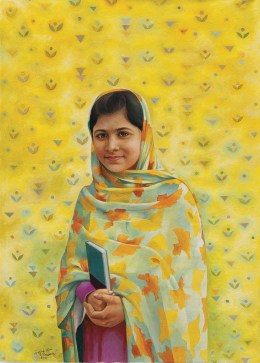

Family friends attribute Malala’s precociousness to her father, a social activist who believes that the education of girls is vital to Pakistan’s future. Ziauddin Yousafzai opened Khushal School and College 17 years ago with the aim of building a new generation of female leaders. Samar Minallah Khan, a documentary filmmaker who got to know the Yousafzais in 2010 when she made a film about the school, was astounded by the ambition and character of the girls she met. “Each and every girl in that school is a Malala,” says Khan, “and the credit goes to her father and the teachers and the principal.”

In September 2008, as the Pakistani Taliban gained a significant foothold in Swat and started enforcing their strict interpretations of Islamic law, Yousafzai took Malala to the provincial capital of Peshawar for an event at the city’s press club. There, in front of the national press, the 11-year-old gave a speech titled “How Dare the Taliban Take Away My Basic Right to Education?” The speech was well received, but many worried that confronting the Taliban so brazenly might put Malala in danger. “People said to me, ‘How can you let her do this?’” Yousafzai told a reporter at the time. “We needed to stand up,” he reasoned.

Some believe that Malala was simply not old enough to make what were essentially life-or-death decisions. “I think Zia was imposing his own thoughts about girls’ education on her,” says Dr. Mohammad Ayub, a psychiatrist from Swat who manages the hospital where Malala was taken immediately after the shooting. Malala, he says, “was like a suicide bomber, brainwashed into putting herself in danger. Child prostitutes, child soldiers, child laborers and child heroes — they are all exploited children, in my opinion, and it shouldn’t be allowed.” People who know Malala personally, however, insist that she knew what she was doing. “No one on this earth can dictate to Malala,” says Khan.

(PHOTOS: Head Of Her Class: A Look at Malala’s School Work)

In late 2008, the BBC Urdu service proposed to Yousafzai that one of his students blog anonymously about what it was like going to school under Taliban rule. Malala volunteered to do it herself. She dived into the new project with dark humor. “On my way from school to home I heard a man saying, ‘I will kill you,’” she wrote on Jan. 3, 2009. “I hastened my pace … to my utter relief he was talking on his mobile and must have been threatening someone else over the phone.”

Even though her diary entries were anonymous, Malala apparently had few qualms about speaking openly to a national audience. On the evening of Feb. 18, 2009, she was attending an anti-Taliban protest with her father in Swat’s capital, Mingora, where she spied broadcaster Hamid Mir, who was in town reporting. She ran up to him and asked to be on his show. Intrigued, he put her on. “All I want is an education,” she told Mir and his audience. “And I am afraid of no one.”

By the time the Taliban were driven from Swat seven months later, Malala had become a visible advocate for girls’ education. She campaigned to raise government spending on schools (at the moment it’s a miserable 2% of GDP, compared with the U.S. average expenditure of about 5.4%) and encouraged families to break with tribal tradition and allow their daughters to attend classes. A number of schools were renamed in her honor. She met with the late Richard Holbrooke, then the U.S. special envoy to Pakistan and Afghanistan, to plead for assistance for Pakistani schools.

But in December 2009, Malala, whose identity as the BBC blogger had been something of an open secret for several months, was publicly identified by her father, who was proud of her accomplishments. The leader of the Swat Taliban, Maulana Fazlullah, decided it was time to silence Malala and sent two men to kill her. “We did not want to kill her, as we knew it would cause us a bad name in the media,” Sirajuddin Ahmad, a senior commander and spokesman for the Swat Taliban, told TIME. “But there was no other option.”

When the converted truck that serves as the Khushal school bus came to a stop on Oct. 9 this year, few of the 14 girls and three teachers crammed onto the two long benches inside even noticed. They were too busy chatting about the exams they had just completed. Shazia Ramzan, a 13-year-old sitting next to Malala near the open back of the truck, was the first to see the gunman. “Which one is Malala?” he barked. Terrified, the girls fell silent. “I think we must have looked at her,” admits Shazia. “We didn’t say anything, but we must have looked, because then he shot her.” Shazia screamed when she saw Malala slump forward. The gunman turned and shot Shazia and another girl, neither fatally. The gunman fled.