Tim Cook has the decidedly nontrivial distinction of being the first CEO of Apple since the very first to come to power without blood on his hands. For most of its history, Apple has had a succession problem: it had no internal mechanism for transferring power from one CEO to the next without descending into civil war in between. “Each time,” Cook says, “the way that the CEO was named was when somebody got fired and a new one came in.”

This clearly bothered Steve Jobs, because he spoke to Cook about it shortly before he died. “Steve wanted the CEO transition to be professional,” Cook says. “That was his top thing when he decided to become chairman. I had every reason to believe, and I think he thought, that that was going to be in a long time.” As we now know, it wasn’t.

(Interactive Timeline: Tim Cook and the Rise of Apple)

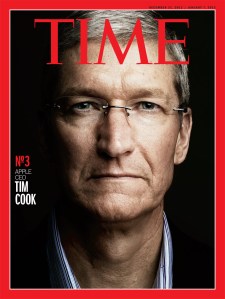

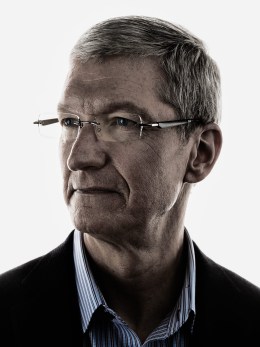

As long as he was handpicking his successor, you’d think Jobs would have chosen someone in his own image, but he and Cook, who was Jobs’ COO at Apple, are in a lot of ways diametrical opposites. Jobs was loud, brash, unpredictable, uninhibited and very often unshaven. Cook isn’t. He doesn’t look like the CEO of Apple, he looks more like an Apple product: quiet, tidy, carefully curated, meticulously tooled and at the same time strangely warm and inviting. He doesn’t look like Jobs, he looks like something Jobs would have made. Cook’s flawless cap of white hair could have been designed by Jony Ive and fabricated in China out of brushed aluminum.

And like an Apple product, Cook runs smooth and fast. When Jobs died on Oct. 5, 2011, of pancreatic cancer, there were questions about whether Cook could lead Apple. Some, myself included, wondered whether Apple was even a viable company without Jobs. Since then Cook has gone about his business apparently unintimidated by his role as successor to one of the greatest innovators in history. Cook’s record hasn’t been flawless, but he has presided in a masterly way over both a thorough, systematic upgrading of each of the company’s major product lines and a run-up in the company’s financial fortunes that can only be described as historic.

On the day Jobs died, Apple was valued at $351 billion; at press time its market cap stood at $488 billion, more than that of Google and Microsoft. That’s and as in plus: Apple is now worth significantly more than those companies combined. Apple’s cash hoard alone comes to more than $120 billion. It was news in 2011 when Apple passed Exxon Mobil to become the world’s most valuable company. Now Exxon Mobil can barely see Apple’s taillights in the distance, across an $83 billion lead.

And Cook has done it his way. Jobs was famously over the top: he came at you from across the room, flashing his lightning-bolt eyebrows, and he browbeat you till you either agreed with him or pretended to, just to make him for God’s sake stop. That’s not how Cook operates. He’s a seducer, a Southern drawler, slow and soft-spoken. He has been observed winking. He doesn’t come at you; he waits for you to come to him. And sooner or later you do, not because you have to but because, dang it, you want to.

Cook himself is reluctant to lean too hard on the contrast. “I think there’s some obvious differences,” he says. (He allows himself a chuckle at the understatement.) “The way we conduct ourselves is very different. I decided from negative time zero — a long time before he talked to me about his decision to pass the CEO title — that I was going to be my own self. That’s the only person that I could do a good job with being.”

(LIST: 10 Key Moments in Apple’s History)

That’s what Jobs wanted. He didn’t want Cook to be a Jobs knockoff. He wanted Cook to be Cook. “He said, ‘From this day forward, never ask what I would do. Just do what’s right.’ I brought up a couple of examples: ‘Suppose A — do you really want me to make the call?’ Yes. Yes! He talked about Disney and what he saw had happened to Disney [after Walt Disney died], and he didn’t want it to happen to Apple.”

Cook does have a few things in common with Jobs. He’s a workaholic, and not of the recovering kind. He wakes up at 3:45 every morning (“Yes, every morning”), does e-mail for an hour, stealing a march on those lazy East Coasters three time zones ahead of him, then goes to the gym, then Starbucks (for more e-mail), then work. “The thing about it is, when you love what you do, you don’t really think of it as work. It’s what you do. And that’s the good fortune of where I find myself.”

(Special Report: The Cult of Apple in China)

Like Jobs, Cook suffers fools neither gladly nor in any other way (except when he has to, i.e., when talking to journalists). Behind the scenes, that measured calm can — if the legends are true — become a merciless coldness that roots out confusion and incompetence. “I’ve always felt that a part of leadership is conveying a sense of urgency in dealing with key issues,” he says. “Apple operates at an extreme pace, and my experience has been that key issues rarely get smaller on their own.” The definitive Tim Cook anecdote involves a meeting he once called about a crisis in China that required a hands-on solution. After 30 minutes, he looked at one executive and said, “Why are you still here?” The man — a sense of urgency having been successfully conveyed — immediately left the meeting, drove directly to the airport and flew to China, without even a change of clothes.

Like Jobs, Cook never shows any doubt in public, either about himself or about Apple, not a scintilla, not for an instant. He rarely strays far from his core message about Apple: that it’s the best, most innovative company in the world, that consumers love it and that it is his privilege to work for it and for them. When speaking about his management style, Cook begins, “CEOs are all packages of strengths and …” He hesitates, looking for some way to reroute the sentence around the word weaknesses. Then he finds it: “and so forth.”

(GALLERY: TIME’s Steve Jobs Covers)

And like Jobs, Cook has reason to think of himself as an outsider, even as he sits at the center of global techno-cool, piling up a considerable personal fortune. (In 2011, Apple awarded Cook a golden-handcuffs package of options potentially worth more than $376 million.) Jobs’ story is well known: he was adopted — the biological son of a Syrian graduate student — and he was a college dropout. Cook’s story is very different but no less singular. He’s highly discreet about his private life, but this much is public record: Cook grew up in a small Alabama town called Robertsdale (pop. 5,402), the son of a shipyard worker. According to a speech Cook gave at Goldman Sachs this year, he worked in a paper mill and an aluminum plant. Jobs was at least middle class and a native son of Silicon Valley. Cook is, by all indications, a working-class kid from the Deep South.

Cook earned a degree in industrial engineering from Auburn University in 1982. From there he did the expected thing: he spent 12 years at IBM, where he showed a flair for a finicky, unglamorous side of the business: manufacturing and distribution. From IBM, Cook bounced to Intelligent Electronics and then in 1997 to Compaq as vice president for corporate materials. Then he did the unexpected thing.

(PHOTOS: A Brief History of the Computer)

Almost immediately after he arrived at Compaq, Cook began to get calls from Apple’s headhunters. Jobs was back from exile — he was pushed out from Apple in 1985, then rehired 12 years later — and he wanted to bring in somebody new to run operations. At that point Apple was generally considered to be in a death spiral — that year alone, it lost a billion dollars — and Cook had no interest whatsoever in moving. But Jobs was a legend in the industry, so Cook sat down with him one Saturday morning in Palo Alto. “I was curious to meet him,” Cook says. “We started to talk, and, I swear, five minutes into the conversation I’m thinking, I want to do this. And it was a very bizarre thing, because I literally would have placed the odds on that near zero, probably at zero.”

Cook was interested in Jobs’ strategy, which he describes using a favorite Cook expression, doubling down: “It was the polar opposite of everyone else’s. He was doubling down on consumer when everybody else was going into enterprise. And I thought it was genius. Compaq was doing so poorly in consumer, didn’t have a clue how to do consumer. IBM had left. Everybody was kind of concluding that consumer business is a loser, and here Steve is betting the company on it.”

It wasn’t just what they were doing at Apple, it was how they were doing it. The culture was different. “I loved the fact that I could disagree with Steve and he wasn’t offended by it.” For his part, Jobs must have seen something in Cook that wasn’t obvious to anybody else: the maverick, the outsider. “I’ve never thought going the way of the herd was a particularly good strategy,” Cook says. “You can be assured to be at best middle of the pack if you do that. And that’s at best.”

Cook got home on Sunday. Jobs offered him the job on Monday. On Tuesday, Cook resigned from Compaq. The same way Ive became Jobs’ trusted lieutenant on the design side, Cook stepped into that role in the less sexy and consumer-facing but equally vital area of manufacturing and distribution.

As COO, Cook was content to be a wizard in the dark art of supply-chain management. As CEO, Cook has had to decloak, to focus on the very public product side, the way Jobs did. When Cook looks back at 2012, that’s where he puts the emphasis. “It’s the most prolific year of innovation ever,” he says. “If you went back and were to watch a compressed movie of it, it’s amazing the products that have come out.”

He is, of course, correct. In 2012, Apple released the iPhone 5, the newly redesigned MacBook Pro, two new iPods and both the third- and fourth-generation iPads, plus the iPad Mini. Apple completely redesigned its flagship media software, iTunes, and added more than 272,000 new apps to the iTunes store. “This year has been an intense year on products,” he says. “Like no other.”

(LIST: 30 Best iPad Apps)

All that is true and amazing and at the same time not 100% surprising. Cook has had the effect on Apple that you’d expect from an operations genius: he’s made all the existing product-improving machinery run even faster and smoother than it already did. The real story of Apple in 2012 may be what Cook has done in China.

Jobs never visited the country where most of Apple’s products are built, at least not in any official capacity, but as a manufacturing guy Cook is an old China hand, and on his watch Apple has broken out as a consumer brand there. The iPhone got Apple inside the Great Wall, and it has proved to be a Trojan horse: Apple products are now a status symbol among the newly affluent. When the iPhone 4S launched there in January, there were near riots outside Apple stores; the iPhone 5 sold 2 million units in China in three days. Overall, Apple’s revenue from China grew by $10 billion in 2012. “It’s a huge market with huge potential,” Cook says, “with an enormous emerging middle class that really wants Apple products. I think it will be our largest market, over time.”

Apple also met with some serious and very public reversals in 2012. The labor practices of its Chinese manufacturing partners’ factories continued to be a source of embarrassment. September saw the distinctly un-Apple-like launch of Apple Maps, which was buggy and reportedly misinformed as to the location of landmarks like Washington’s Dulles International Airport. These were, if nothing else, opportunities for Cook to show off his chops as a swift, steely decisionmaker. Cook arranged for independent audits of Apple’s Chinese factories by the Fair Labor Association, and he toured China and met with Vice Premier Li Keqiang. After the Maps debacle, Cook stepped up and made a public apology, in which he took the extraordinary step of urging consumers to use competitors’ products until Apple got its house in order. He also reshuffled his cabinet, ousting the heads of Apple’s retail and mobile-software divisions.

(LIST: 50 Best iPhone Apps of 2012)

Nevertheless, the market’s faith in Apple has seriously wavered since September, when its stock briefly, ecstatically crested above 700. Apple missed earnings estimates in the third and fourth quarters, and while it remains the world’s most valuable company, its stock has taken a sustained three-month hammering that has left it down 25% from that high point.

There is a babel of opinions among analysts about what this does or doesn’t mean. Some blame Maps. Some think the increasingly ferocious competition in the smart-phone and tablet markets is making investors nervous. Some think Apple has lost its innovative spark. Others say Apple’s numbers are still so huge, who cares if they’re slightly less than the even more huge but essentially arbitrary numbers that Wall Street analysts expected? Apple’s price-earnings ratio hovers around a robust 12. There are commentators who still consider Apple undervalued. But there’s no question that Cook also has plenty of doubters left to convince.

None of this appears to ruffle Cook particularly. “I’ve worked at Apple for 15 years,” he says, “so Apple’s not foreign to me. I don’t mean to sound like it’s all a predictable ride. It’s unpredictable. But it’s always been unpredictable.” He hasn’t altered his personal style any. He remains, like all great Apple products, a paradoxical combination of open and closed, polished and user-friendly but also sealed up tight against anybody who’s curious about what’s inside. You know there are reams of code churning away down there, just below the surface, but you’ll never know exactly what’s going on.

His critics say Cook lacks a true technologist’s vision, but it would be more accurate to say that he has yet to show his hand. Apple finished 2012 with a triumphant record of innovation, but it was innovation with a small i, as in incremental. That’s good enough for an ordinary company, but it’s not what made Apple worth more than Exxon Mobil. The essence of Apple is the quantum leap, the unexpected sideways juke into a heretofore unnoticed and underexploited market — personal computers, digital music players, smart phones, tablet computers. Maybe the next stop is televisions; that’s certainly where the rumor mill is going. But the test for Cook will be to seek out a new category that’s vulnerable to disruption and disrupt the hell out of it.

I ask Cook if he would do that — if that would continue to be Apple’s modus operandi going forward. He smiles, seductively as always, and says, “Yes. Yes. Most definitely.” When that happens, that’s when Cook will show his hand, and we’ll get a look below the surface. He’ll do the unexpected thing and double down on something new. And when he does, that’s when the rest of the world will see what Jobs saw in him.