Tim Cook has the decidedly nontrivial distinction of being the first CEO of Apple since the very first to come to power without blood on his hands. For most of its history, Apple has had a succession problem: it had no internal mechanism for transferring power from one CEO to the next without descending into civil war in between. “Each time,” Cook says, “the way that the CEO was named was when somebody got fired and a new one came in.”

This clearly bothered Steve Jobs, because he spoke to Cook about it shortly before he died. “Steve wanted the CEO transition to be professional,” Cook says. “That was his top thing when he decided to become chairman. I had every reason to believe, and I think he thought, that that was going to be in a long time.” As we now know, it wasn’t.

(Interactive Timeline: Tim Cook and the Rise of Apple)

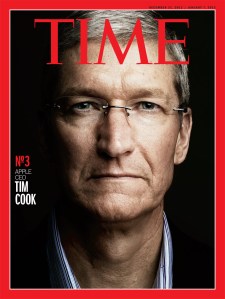

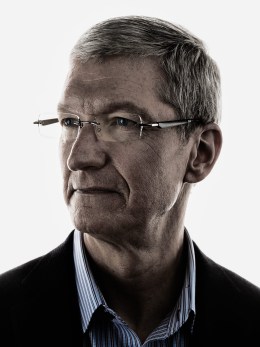

As long as he was handpicking his successor, you’d think Jobs would have chosen someone in his own image, but he and Cook, who was Jobs’ COO at Apple, are in a lot of ways diametrical opposites. Jobs was loud, brash, unpredictable, uninhibited and very often unshaven. Cook isn’t. He doesn’t look like the CEO of Apple, he looks more like an Apple product: quiet, tidy, carefully curated, meticulously tooled and at the same time strangely warm and inviting. He doesn’t look like Jobs, he looks like something Jobs would have made. Cook’s flawless cap of white hair could have been designed by Jony Ive and fabricated in China out of brushed aluminum.

And like an Apple product, Cook runs smooth and fast. When Jobs died on Oct. 5, 2011, of pancreatic cancer, there were questions about whether Cook could lead Apple. Some, myself included, wondered whether Apple was even a viable company without Jobs. Since then Cook has gone about his business apparently unintimidated by his role as successor to one of the greatest innovators in history. Cook’s record hasn’t been flawless, but he has presided in a masterly way over both a thorough, systematic upgrading of each of the company’s major product lines and a run-up in the company’s financial fortunes that can only be described as historic.

On the day Jobs died, Apple was valued at $351 billion; at press time its market cap stood at $488 billion, more than that of Google and Microsoft. That’s and as in plus: Apple is now worth significantly more than those companies combined. Apple’s cash hoard alone comes to more than $120 billion. It was news in 2011 when Apple passed Exxon Mobil to become the world’s most valuable company. Now Exxon Mobil can barely see Apple’s taillights in the distance, across an $83 billion lead.

And Cook has done it his way. Jobs was famously over the top: he came at you from across the room, flashing his lightning-bolt eyebrows, and he browbeat you till you either agreed with him or pretended to, just to make him for God’s sake stop. That’s not how Cook operates. He’s a seducer, a Southern drawler, slow and soft-spoken. He has been observed winking. He doesn’t come at you; he waits for you to come to him. And sooner or later you do, not because you have to but because, dang it, you want to.

Cook himself is reluctant to lean too hard on the contrast. “I think there’s some obvious differences,” he says. (He allows himself a chuckle at the understatement.) “The way we conduct ourselves is very different. I decided from negative time zero — a long time before he talked to me about his decision to pass the CEO title — that I was going to be my own self. That’s the only person that I could do a good job with being.”

(LIST: 10 Key Moments in Apple’s History)

That’s what Jobs wanted. He didn’t want Cook to be a Jobs knockoff. He wanted Cook to be Cook. “He said, ‘From this day forward, never ask what I would do. Just do what’s right.’ I brought up a couple of examples: ‘Suppose A — do you really want me to make the call?’ Yes. Yes! He talked about Disney and what he saw had happened to Disney [after Walt Disney died], and he didn’t want it to happen to Apple.”

Cook does have a few things in common with Jobs. He’s a workaholic, and not of the recovering kind. He wakes up at 3:45 every morning (“Yes, every morning”), does e-mail for an hour, stealing a march on those lazy East Coasters three time zones ahead of him, then goes to the gym, then Starbucks (for more e-mail), then work. “The thing about it is, when you love what you do, you don’t really think of it as work. It’s what you do. And that’s the good fortune of where I find myself.”

(Special Report: The Cult of Apple in China)